In the streets of Drohobycz

The man walks down the street at a rapid pace, as if escaping from an earthquake, one shoulder higher than the other, his body twisted by a pain in the leg. Behind him, the stalls of the market of Drohobycz are closing, damaged fruits cover the soil, dogs rummage through the waste in the slots of the paving. The women fold the plastic bags used a thousand times, folded and unfolded, crumpled and smoothed again.

Drohobycz does not hide its ruins, it exposes them with an unconscious pride. The synagogue only welcomes the birds, the rain and the wind, no strange furniture troubles it any more, nobody can enter it; only a pulley suspended in front of the darkness protects it from the last raiders.

A bell strikes the hour as we go up the street towards the highest point of Drohobycz.

Houses, streets, squares, people. A frightful face filling the whole square: Bandera. An old woman begging. How much imaginaton was necessary to enchant such a city! How much insomnia to build a dream from these rundown facades!

The bell of the nearby church indicates the hour again, the sun is already set, crows are circling above the square, a man comes out from the bakery, one shoulder higher than the other, black suspendesr on his checkered black and white shirt, he brings a large bread in front of himself as if he held a dead child, his steps directed towards the place where SS officer Günther shot two bullets into the head of the Jew of SS officer Landau, because this latter had killed his Jew. A little revenge between friends.

Clouds, dark trees in the park behind, the smell of warm bread, and hundreds of screaming crows in the sky.

A woman is sweeping at the corner of a street.

In the cities I have always liked the dust, which preserves your footsteps, which covers and hides and steals. I love the gray which highlights the stuccos of the facades; the peeling plaster; the brick shedding its coat; the statues which lost their arms and whose gaze is fixed to the emptiness. I love the emptiness, the fences blocking the path where you want to go. You would like to go straight, but every moment your feet stumble over cobblestones, a pile of debris, they turn to the right and to the left as if right there, between the stones, in the cracks of the pavement there were another street, which we don’t see, but it has always been there, and sometimes it flutters and beckons. For a fragment of a second, the city takes us at the ankles and makes us waver. In that moment there appears a familiar and unknown city, written into the dust of time.

A woman is sweeping, for hours and hours.

In the streets of Lwów

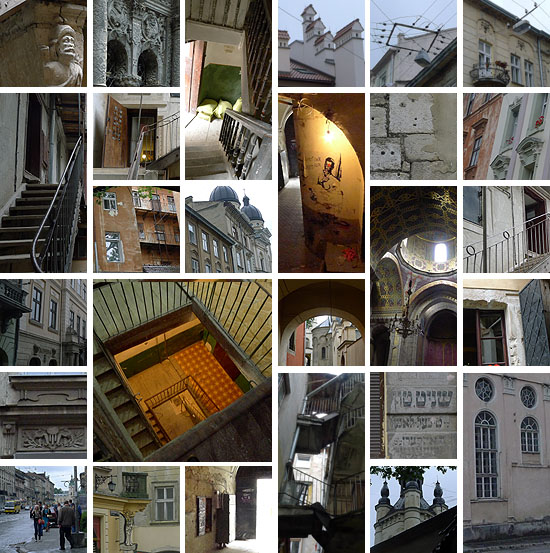

Lwów is a labyrinth which does not give a clue to itself. I get lost in it.

The plan of the city seems to be of an exemplary regularity, a perfect square grid, as the Renaissance loved it, with the old market place and the town hall tower as its starting point. From this square grid, the roads drawn in a star pattern in the 19th century start out towards the suburbs like a fan that opens and then closes before the traveler. From the heart of the city to the periphery, and from the Baroque world to the Art Nouveau world the facades show so many stucco works, the roofs so many perfect curves, the colors match without error, each house play its own variation on some simple common themes. Every street is thus both multiple and unique. However, from one side of the square to the other, different worlds are pressed close together, visit, envy and attack each other – Germans, Poles, Ukrainians, Armenians, Jews. Each of them constructed and sometimes even closed with a wall their own spaces, and marked its borders with inscriptions carved in stone or painted on the walls, like so many kabbalistic signs written in a common territory. And one careless moment is enough, when you turn around the corner, pass from one yard to another, open the door on a dark corridor, to be caught in the labyrinth and to get lost.

I also went through the streets, my feet followed the tracks and my eyes the arrows, I climbed the stairs and followed the corridors, but amid all the foreign languages I had to affront and in which I was lost, the only thing I understood was the echo of Prospero’s voice at the moment of taking leave of his island:

You do look, my son, in a moved sort,

As if you were dismay’d: be cheerful, sir.

Our revels now are ended. These our actors,

As I foretold you, were all spirits and

Are melted into air, into thin air:

And, like the baseless fabric of this vision,

The cloud-capp'd towers, the gorgeous palaces,

The solemn temples, the great globe itself,

Ye all which it inherit, shall dissolve

And, like this insubstantial pageant faded,

Leave not a rack behind. We are such stuff

As dreams are made on, and our little life

Is rounded with a sleep.

In the waking day I watch the city from my window. Lwów is still wrapped in sleep, the silence is only broken every fifteen minutes by the bells of a church. What does really remain from the palaces and towers and solemn temples when they who built them, who worked there, raised children, invented objects, printed books, solved mathematical problems, disappear? Several worlds were pressed close together – Germans, Poles, Ukrainians, Armenians, Jews –, and each of them became ghosts which still haunt in the places after their bodies were massacred, deported, displaced. And they who now live in these places and bring there life are but recent guests – without doubt, displaced people themselves.

We spend so many hours in Lwów, walking through streets and squares, listening such stories, evoking the ghosts, solving the string of the sack of dreams, looking for clues between the stones, where time has created a Pompeii of Galicia.

There was the synagogue. Now a child runs forward from the emptiness on its place. The site is occupied by weeds and a tree full of fruits.

Once this city also had a river, but it too has disappeared – at least once a war was not in vain. The Poltva, which traced a loop around the old town, was covered in the early 20th century, and a promenade established over it, a large grove, where we still can imagine the music pavilions and the beauties walking in long dresses and elegant hats. But a river is not only made of freshness and reflections, currents and sandbars. It also gives directions to a city, indicating the right bank and the left bank, designating the cardinal points, showing the way to the sea and to the mountains. Its erasure seals the labyrinth: a city without a thread of Ariadne – or almost.

Zhovkva

In the middle of nowhere, a town to which no road leads. A city that accumulates domes, pinnacles and towers. We circle around it, we move away to better reach it, it slips away from us when we see it the best from far across the plain.

Entering through the city gate, a disproportionate square, where thousands of soldiers could line up in war times. A disproportionate square where hundreds of merchants, coming from hundreds of kilometers around, could set up their stalls in peace times. A space large enough to accommodate and mix with each other Ukrainians, Jews and Poles, Turks and Armenians. A city at the gates of a kingdom, a city to secure its power, a city which was a royal residence in the time of King John III Sobieski, in the 17th century.

It is also a city of churches, for everyone his own, where they head in neat clothes on Sunday morning.

Children with serious faces in white robes come out in a row under the rain, disappearing for a short time off the eyes of the faithful, urged by the priest following them.

It’ only her who is missing from this multiple universe: the synagogue behind the planks, as a faded rose, her walls surround only the void left behind by the explosion that wanted to destroy her in 1943. At a certain point there was a building site here, they replastered the walls, healed the cracks, and then all that stopped. A yellow cat is sneaking towards the rusty containers surrounding the site as abandoned sarcophagi.

An old woman passes by, a greengrocer is waiting for customers. The rain slowly returns. I go through the streets.

How to get lost in Zhovkva, when all roads lead to the same single square? Where to get lost in ths emptiness? How do they live, the inhabitants of Zhovkva, how do live these young ladies dressed for Sunday, leading their children to the patisserie after the Mass, and how do live they who remain on the balconies, waiting for the hour of the Sunday lunch?

An old man stops me. So many words exchanged, so many snippets of life in a few minutes. A hand with fingers cut off, one phalanx here and two phalanxes there, touching and retouching my hand, grabbing my arm at every question, at every word I do not understand. Names, ages, places, Napoleon and Jules Verne who traveled around the world without having ever left Nantes. A life drawn by the hand on the rain-coated windscreen of a car: a map of the Ukraine, one large circle. In the circle, one point for Lwów, another for Odessa, and a third one for the small village where he was born. In the Crimea? No, he draws another circle for the Crimea, a very small one, like an island under Odessa. Well, the third point is near Kherson. “Have you ever been to Kherson?”

His friend arrives, moon-faced, with a toothless mouth, croaking in an entirely different language. The two of them start a moment of theatrical performance, with gestures and grimaces, swaying with the whole body, an almost Neapolitan pantomime dotted with inarticulate shouts echoing each other. A gorgeous drunkenness already on Sunday morning.

I move off, it definitely rains now.

Dogs

Once you arrive in the Eastern part of Europe, say once past the Bug, you encounter them on the street corners, under the cars or behind the trucks, lying on the debris that pile up at the doors of the houses, these black and white dogs with low legs, oversized ears and intelligent eyes, patiently watching you approaching them, though ready to flee if necessary at the first hostile gesture.

Despite some small local differences, it seems that they all belong to the same breed. The experts still debate the exact origin of this dog which they call sometimes Carpathian Terrier (see here above), Balkan Terrier, Caucasus Terrier, or often simply Street or Court Terrier. Although quite peaceful and attached to people, these dogs most probably came to Europe in the 4th or 5th century with the invasion of the Huns: so strictly speaking, they should be called Hun Terriers, or Hunnies in the colloquial language. In the Caucasus they dispute this origin, as the Huns never crossed the area during their long journey westward. However, close relatives of these Hun dogs certainly came there via Persia, together with the Turkomans and Mongols. William of Rubruck, visiting Karakorum in 1254, refers to these animals who in daytime run between the legs of the horses and in the night slept on their back if the ride continued. The importance of these dogs in certain Mongol and Turkoman tribes was not negligible: alongside the Karakoyunlu, that is, Black Sheep clan, allegedly there was also a Black Dog clan, whose warriors wore the skins of black and tan dogs on their spears. However, this information must be taken with caution, as the passage of Babur’s memoirs mentioning them is of questionable origin, and seems to come from a later author whose Chaghatai Turk was quite altered by the Mughal influence.

The fact is that today these dogs, although largely independent, generally live in the streets, within easy reach of people and are closely linked to them. Some of them are also capable of higher feelings than many humans, for example this one in Drohobycz, which for so many years has been waiting with the eyes fixed on the road coming from the forest, where the black cab bringing Bruno Schulz back to the city should once appear.

Others, like this young Carpathian Terrier, seem to lend to the people, their movements and adventures, a constant interest, certainly not devoid of fun.

And the people willingly return it.