It would be a guaranteed dropout question in any quiz: where does a statue of Attila the Hun stand today? One could only guess: in Transylvania? In ancient Upper Hungary? In Sopron? In Óbuda? In Mongolia? On the battlefield of Catalaunum? In China, in the former capital of the Huns?

The correct answer is: twenty kilometers from Vienna, in the tiny Austrian town of Tulln.

Nowadays the late descendants of the Huns only make expeditions to the Praskac of Tulln, the richest nursery of Kukania for English roses and other Western treasures unknown in Hunland. Ancient Huns, however, used to come here for quite different flowers.

According to the Nibelung Epic, Attila, the king of the Huns received here his bride Kriemhild coming by boat from Passau:

ein stat bi tvonowe / lit in osterlant

ein stat bi tvonowe / lit in osterlant

div ist geheizen tvln / da wart ir bechant

vil manich site vremede / den si e nie gesach

si enpfiengen da genvge / den sit leit von ir gesach

vor eceln dem chvenege / ein ingesinde reit

vro vnd vil riche / hoefsh vnt gemeit

wol vier vnd zweinzech fversten / tiwer vnd her

daz si ir vrowen saehen / davon en gerten si niht mer

zwene fvrsten riche / als vns daz ist geseit

bi der frvn gende / trvgn iriv chleit

da ir der chvenich ecel / hin engegen gie

da si den fvrsten edele / mit chvsse gvetelich enpfie

A city by the Danube / in Osterland doth stand,

Hight the same is Tulna: / of many a distant land

Saw Kriemhild there the customs, / ne’er yet to her were known.

To many there did greet her / sorrow befell through her anon.

Before the monarch Etzel / rode a company

Of merry men and mighty, / courteous and fair to see,

Good four-and-twenty chieftains, / mighty men and bold.

Naught else was their desire / save but their mistress to behold.

As is to us related, / did there high princes twain

By the lady walking / bear aloft her train,

As the royal Etzel / went forward her to meet,

And she the noble monarch / with kiss in kindly wise did greet.

Such a historical chance cannot be missed by a small Austrian town of ten thousand inhabitants. Although Tulln has just recently (2001) erected a statue – a copy of the equestrian statue in the Capitolium – to Marcus Aurelius – “in order it might recall the memory of several centuries of Roman presence at the banks of the Danube” –, as well as to the great son of the town Egon Schiele (2000) – whose memory until then was only recalled by the town prison, where he condescended to serve his sentence, and which was then transformed into a Schiele Museum with open air beer pub and a gorgeous vista on the Danube – but having been mentioned in the Nibelungenlied is a whole other story!

The town has therefore given commission to the Russian sculptor Mikhail Nogin – who happens to have been the creator of the previous two statues as well – to erect a monument, in the form of a sculptural group on the presumptive site of that historical encounter, the desolate bank of the Danube behind the monastery of the Minorites, to the marching in of Tulln into German epic poetry. With this “Projekt” – as Landeshauptmannstellvertreter Ernest Gabmann formulated it with untranslatable German perfection – “wurde ein wertvoller städtebaulicher Akzent gesetzt”, and furthermore – a hardly negligible point of view – “wurden rund 160 Parkplätze in der Innenstadt von Tulln geschaffen, wodurch das Zentrum attraktiviert und eine Erhöhung der Kundenfrequenz erreicht werden soll”.

The statue unveiled in 2005 which, instead of being trivially mentioned as a “Denkmal” – Österreich ist anders! – is called a “Bronzeskulpturen-Dokumentation,” consists of three parts. In the forefront one can read the verses of the Nibelung Epic about Tulln freshly written on the open page of a large bronze book placed on a rustic slab – the quill of the bronze goose is still laying on the bronze page. Behind the book, the jets of water of the fountain shaped by “Wasserbildhauer” (haben Sie’s mal probiert, Wasser zu hauen?) Hans Muhr, repeat on a larger scale the double arch of the open book, subliming it into an unmaterial and timeless metaphor as if it were, while from behind the vapour of the water, like from the mist of the past, the historical vision emerges. A straight talk. The citizen looks at it and says: “I got it. That one there comes out of this one here, as if it were. Art, isn’t it.” And thus having succesfully absolved the component “art” of his duty, with peaceful heart he goes on to behold the history.

Kriemhild, coming from the left, from the direction of Passau is accompanied by the Markgraf of Osterland – today’s Austria – Rüdiger von Bechelaren and by the other “high princes twain” mentioned in the epic, to Attila waiting for her on the right side, in the direction of Hunnia. Behind the Hun king there stands his brother Buda, as well as two German princes living in exile in the Hun court, Dietrich von Bern and Gibich. The queue is ended by the little child of Attila, Csaba – according to the inscription he is Aladár, but this latter will be actually the son of Kriemhild – swinging his wooden sword and peeping curiously from behind the cloak of Gibich at his future stepmother.

Finally, behind Csaba – rigorously from the direction of Hunnia – a shocked bronze rat is watching the never seen multitude.

The correct answer is: twenty kilometers from Vienna, in the tiny Austrian town of Tulln.

Nowadays the late descendants of the Huns only make expeditions to the Praskac of Tulln, the richest nursery of Kukania for English roses and other Western treasures unknown in Hunland. Ancient Huns, however, used to come here for quite different flowers.

According to the Nibelung Epic, Attila, the king of the Huns received here his bride Kriemhild coming by boat from Passau:

ein stat bi tvonowe / lit in osterlant

ein stat bi tvonowe / lit in osterlantdiv ist geheizen tvln / da wart ir bechant

vil manich site vremede / den si e nie gesach

si enpfiengen da genvge / den sit leit von ir gesach

vor eceln dem chvenege / ein ingesinde reit

vro vnd vil riche / hoefsh vnt gemeit

wol vier vnd zweinzech fversten / tiwer vnd her

daz si ir vrowen saehen / davon en gerten si niht mer

zwene fvrsten riche / als vns daz ist geseit

bi der frvn gende / trvgn iriv chleit

da ir der chvenich ecel / hin engegen gie

da si den fvrsten edele / mit chvsse gvetelich enpfie

A city by the Danube / in Osterland doth stand,

Hight the same is Tulna: / of many a distant land

Saw Kriemhild there the customs, / ne’er yet to her were known.

To many there did greet her / sorrow befell through her anon.

Before the monarch Etzel / rode a company

Of merry men and mighty, / courteous and fair to see,

Good four-and-twenty chieftains, / mighty men and bold.

Naught else was their desire / save but their mistress to behold.

As is to us related, / did there high princes twain

By the lady walking / bear aloft her train,

As the royal Etzel / went forward her to meet,

And she the noble monarch / with kiss in kindly wise did greet.

Such a historical chance cannot be missed by a small Austrian town of ten thousand inhabitants. Although Tulln has just recently (2001) erected a statue – a copy of the equestrian statue in the Capitolium – to Marcus Aurelius – “in order it might recall the memory of several centuries of Roman presence at the banks of the Danube” –, as well as to the great son of the town Egon Schiele (2000) – whose memory until then was only recalled by the town prison, where he condescended to serve his sentence, and which was then transformed into a Schiele Museum with open air beer pub and a gorgeous vista on the Danube – but having been mentioned in the Nibelungenlied is a whole other story!

The town has therefore given commission to the Russian sculptor Mikhail Nogin – who happens to have been the creator of the previous two statues as well – to erect a monument, in the form of a sculptural group on the presumptive site of that historical encounter, the desolate bank of the Danube behind the monastery of the Minorites, to the marching in of Tulln into German epic poetry. With this “Projekt” – as Landeshauptmannstellvertreter Ernest Gabmann formulated it with untranslatable German perfection – “wurde ein wertvoller städtebaulicher Akzent gesetzt”, and furthermore – a hardly negligible point of view – “wurden rund 160 Parkplätze in der Innenstadt von Tulln geschaffen, wodurch das Zentrum attraktiviert und eine Erhöhung der Kundenfrequenz erreicht werden soll”.

The statue unveiled in 2005 which, instead of being trivially mentioned as a “Denkmal” – Österreich ist anders! – is called a “Bronzeskulpturen-Dokumentation,” consists of three parts. In the forefront one can read the verses of the Nibelung Epic about Tulln freshly written on the open page of a large bronze book placed on a rustic slab – the quill of the bronze goose is still laying on the bronze page. Behind the book, the jets of water of the fountain shaped by “Wasserbildhauer” (haben Sie’s mal probiert, Wasser zu hauen?) Hans Muhr, repeat on a larger scale the double arch of the open book, subliming it into an unmaterial and timeless metaphor as if it were, while from behind the vapour of the water, like from the mist of the past, the historical vision emerges. A straight talk. The citizen looks at it and says: “I got it. That one there comes out of this one here, as if it were. Art, isn’t it.” And thus having succesfully absolved the component “art” of his duty, with peaceful heart he goes on to behold the history.

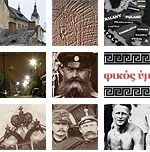

A Rezeptions-Dokumentation of the Bronzeskulpturen-Dokumentation

from digicamfotos.de

from digicamfotos.de

Kriemhild, coming from the left, from the direction of Passau is accompanied by the Markgraf of Osterland – today’s Austria – Rüdiger von Bechelaren and by the other “high princes twain” mentioned in the epic, to Attila waiting for her on the right side, in the direction of Hunnia. Behind the Hun king there stands his brother Buda, as well as two German princes living in exile in the Hun court, Dietrich von Bern and Gibich. The queue is ended by the little child of Attila, Csaba – according to the inscription he is Aladár, but this latter will be actually the son of Kriemhild – swinging his wooden sword and peeping curiously from behind the cloak of Gibich at his future stepmother.

Finally, behind Csaba – rigorously from the direction of Hunnia – a shocked bronze rat is watching the never seen multitude.

From the sinking ship save us, O Lord!

Captains remain the last

The composition is a monumental postmodern gag which – following the widespread recipe of the postmodern gag – starts from easily identifiable traditional frame topoi just in order to deny and ridicule them in the details. This genre is the great encounter of the artist with father complex and of the snobbish petty bourgeois, where both find their pleasure in the systematic emptifying and caricaturing of the exalted topos of the past. And both of them gain an additional bonus as well: the bourgeois an art easy to consume but held in high esteem (“traditional forms in the individual orchestration of the artist”), while the artist the delight of jeering at the bourgeois who consumes and esteems his gag as art. The overdetailed hyperrealism, the affected gestures and the grotesque expression of the figures of the majestic sculptural group recall the characters of cartoons and comics, thus offering an easy clue to the reception of the work of art which is even more enhanced by the genre figures (already qualified as an “opium for the people” by Schopenhauer). The soul of Hundertwasser is hovering above the waters of the fountain.

Incidentally, in the same period Nogin created the statue of another Asian monarch as well, that of Heydar Aliev, President of Azerbaijan. Its erection in the same year of 2005 was heralded by such electronic media like the Day.Az, the Nash Vek (“He left a memory made not with hands...”), or the Azerbajdzhanskaya Izvestiya (“The love of the people is eternal”). The statue standing on a pedestal made of Chinese and Brazilian granite in the Aliev Park established for this purpose was modeled by Nogin in collaboration with Russian artist Salavat Scherbakov, and prepared in the foundry of Smolensk, as it was bitterly commented on the forum of the Azeri AzTop:

was modeled by Nogin in collaboration with Russian artist Salavat Scherbakov, and prepared in the foundry of Smolensk, as it was bitterly commented on the forum of the Azeri AzTop:

Выходит у нас нет гранита, нет скульпторов и нет местечка, где его можно изготовить. Радует то, что хоть деньги у нас на это есть.

It is evident therefore that we have no granite, no sculptors, and no place where it could be prepared. I’m happy, however, that at least we have money for it.

This is of course not entirely true for Tulln, for the Nibelung group was most probably moulded in the same workshop where the two previous statues, that is in the Walter Rom Kunstgiesserei of Tirol, whose professional website offers a flash presentation of the process of moulding well worth to watch.

Heydar Aliev is also renowned for being the first leader of a post-Soviet state that has managed to pass on his power to his son. Attila was not so successful. His son Csaba will be defeated precisely by the son of Kriemhild Aladár, who himself will remain dead on the battlefield.

Kriemhild here, in Tulln does not yet know anything about this, although her ambiguous face gives the semblance as if she already had some preliminary idea about that fatal nosebleed. Being au courant thanks to the Moscow tabloids we happily share with you the secret that this face was borrowed from Varvara, the popular estrade singer of Moscow. An issue of 2004 of the Megapolis-Ekspress has published in the column “Kaleydoskop” its true story that was “narrated by Varvara like a fairy-tale”:

Kriemhild here, in Tulln does not yet know anything about this, although her ambiguous face gives the semblance as if she already had some preliminary idea about that fatal nosebleed. Being au courant thanks to the Moscow tabloids we happily share with you the secret that this face was borrowed from Varvara, the popular estrade singer of Moscow. An issue of 2004 of the Megapolis-Ekspress has published in the column “Kaleydoskop” its true story that was “narrated by Varvara like a fairy-tale”:

“When my director Edik told me that the world famous artist Mikhail Nogin came to us to create a statue of me, my first thought was that we were in a scene of candid camera. What kind of a statue? But the sculptor persisted, and came personally to show the sketches of the monument to Eduard.” Varvara then accepted to visit Nogin in his impressive studio apartment. “Mr. Nogin then began: Every German knows the “Song about the Nibelungs”, whose last version was composed in the 12th century. The characters of this epic are historical figures like Attila, the knight-king of the Huns, his brother Buda, Dietrich von Bern, ambassador Rüdiger and king Gibich, and not least the queen of the Burgunds, the intriguing Kriemhild. However, we have no authentic portrait of any of these personalities. I have to join all these figures in a majestic composition that will stand in the Austrian crook of the Danube, in the town of Tulln, but until now I have not found any female face amongst historical portraits or my own acquaintances that could be the model of the queen. But then I saw a clip in the TV. I did not know the name of the singer, but I was touched by the music, because it somehow bore resemblance to this Celtic [!] epic. And then I looked at her face, and my heart gave a leap. I’ve found my queen! The figure has been finished for a long time, but her face is still temporary. – Mr. Nogin pointed at a monumental statue. – If you agree, let us fix an appointment. If you pose for me, the queen will bear your face. – What a strange proposal! the stunned Varvara said. We have recently married with my husband in an Orthodox cathedral on the bank of the Danube. And although I of course do not know the “Song about the Nibelungs”, but in all my life I felt an attraction to Gothic art and to old castles. ... Even in my songs I draw from the cults of the ancient hunters and fishermen, and I bear the clothes of the ancient Slavs. Precisely this makes Varvara different! And you have felt this! How peculiar! – What is peculiar is that coming home to Moscow I have seen precisely you on the TV. I do not work too much in Russia. I have one statue in the cathedral of Christ the Saviour, but all my major works are in Austria. For example, the statue of Marcus Aurelius ... But the monument in the crook of the Danube will be the main work of my life. We’ve designed an unusual illumination around it, and music will emanate from every part of the statue, the rumble of vehicles and clash of weapons – the illusion of full life. I’m sure that this work will survive for centuries. And the more than three meter high “Varvara” will stand there, looking far away, through ages, fogs and rains.”

We have recently married with my husband in an Orthodox cathedral on the bank of the Danube. And although I of course do not know the “Song about the Nibelungs”, but in all my life I felt an attraction to Gothic art and to old castles. ... Even in my songs I draw from the cults of the ancient hunters and fishermen, and I bear the clothes of the ancient Slavs. Precisely this makes Varvara different! And you have felt this! How peculiar! – What is peculiar is that coming home to Moscow I have seen precisely you on the TV. I do not work too much in Russia. I have one statue in the cathedral of Christ the Saviour, but all my major works are in Austria. For example, the statue of Marcus Aurelius ... But the monument in the crook of the Danube will be the main work of my life. We’ve designed an unusual illumination around it, and music will emanate from every part of the statue, the rumble of vehicles and clash of weapons – the illusion of full life. I’m sure that this work will survive for centuries. And the more than three meter high “Varvara” will stand there, looking far away, through ages, fogs and rains.”

The enthralling song – as it was made explicit in another interview by Varvara – was the Grezy lyubvi (Dreams of Love). Unfortunately we could not see the clip, but from the graphics of Varvara’s site we can imagine what was that visual world that Nogin felt akin to his own.

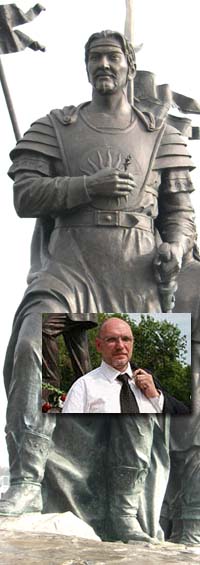

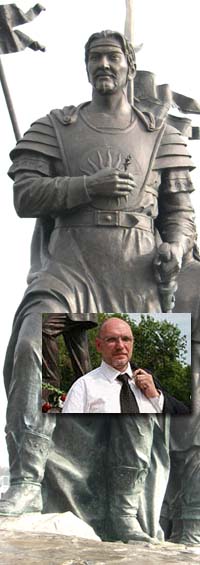

And if it was established that one of the main figures was a portrait, we cannot brush aside the idea that the other one was it as well, namely that of the creator himself – whom we see here on the small picture at the inauguration of his monument to Vrubel in Omsk –, in the main character of the main work of his life. Is it possible that in the figures of the Burgundian Kriemhild and Attila the Hun – or, to borrow the original metaphor of Landeshauptmannstellvertreter Gabmann, in the encounter of East and West – actually two celebrities of the Moscow art scene make a rendezvous in Tulln, on the bank of the Danube?

Incidentally, in the same period Nogin created the statue of another Asian monarch as well, that of Heydar Aliev, President of Azerbaijan. Its erection in the same year of 2005 was heralded by such electronic media like the Day.Az, the Nash Vek (“He left a memory made not with hands...”), or the Azerbajdzhanskaya Izvestiya (“The love of the people is eternal”). The statue standing on a pedestal made of Chinese and Brazilian granite in the Aliev Park established for this purpose

was modeled by Nogin in collaboration with Russian artist Salavat Scherbakov, and prepared in the foundry of Smolensk, as it was bitterly commented on the forum of the Azeri AzTop:

was modeled by Nogin in collaboration with Russian artist Salavat Scherbakov, and prepared in the foundry of Smolensk, as it was bitterly commented on the forum of the Azeri AzTop:Выходит у нас нет гранита, нет скульпторов и нет местечка, где его можно изготовить. Радует то, что хоть деньги у нас на это есть.

It is evident therefore that we have no granite, no sculptors, and no place where it could be prepared. I’m happy, however, that at least we have money for it.

This is of course not entirely true for Tulln, for the Nibelung group was most probably moulded in the same workshop where the two previous statues, that is in the Walter Rom Kunstgiesserei of Tirol, whose professional website offers a flash presentation of the process of moulding well worth to watch.

Heydar Aliev is also renowned for being the first leader of a post-Soviet state that has managed to pass on his power to his son. Attila was not so successful. His son Csaba will be defeated precisely by the son of Kriemhild Aladár, who himself will remain dead on the battlefield.

Kriemhild here, in Tulln does not yet know anything about this, although her ambiguous face gives the semblance as if she already had some preliminary idea about that fatal nosebleed. Being au courant thanks to the Moscow tabloids we happily share with you the secret that this face was borrowed from Varvara, the popular estrade singer of Moscow. An issue of 2004 of the Megapolis-Ekspress has published in the column “Kaleydoskop” its true story that was “narrated by Varvara like a fairy-tale”:

Kriemhild here, in Tulln does not yet know anything about this, although her ambiguous face gives the semblance as if she already had some preliminary idea about that fatal nosebleed. Being au courant thanks to the Moscow tabloids we happily share with you the secret that this face was borrowed from Varvara, the popular estrade singer of Moscow. An issue of 2004 of the Megapolis-Ekspress has published in the column “Kaleydoskop” its true story that was “narrated by Varvara like a fairy-tale”:“When my director Edik told me that the world famous artist Mikhail Nogin came to us to create a statue of me, my first thought was that we were in a scene of candid camera. What kind of a statue? But the sculptor persisted, and came personally to show the sketches of the monument to Eduard.” Varvara then accepted to visit Nogin in his impressive studio apartment. “Mr. Nogin then began: Every German knows the “Song about the Nibelungs”, whose last version was composed in the 12th century. The characters of this epic are historical figures like Attila, the knight-king of the Huns, his brother Buda, Dietrich von Bern, ambassador Rüdiger and king Gibich, and not least the queen of the Burgunds, the intriguing Kriemhild. However, we have no authentic portrait of any of these personalities. I have to join all these figures in a majestic composition that will stand in the Austrian crook of the Danube, in the town of Tulln, but until now I have not found any female face amongst historical portraits or my own acquaintances that could be the model of the queen. But then I saw a clip in the TV. I did not know the name of the singer, but I was touched by the music, because it somehow bore resemblance to this Celtic [!] epic. And then I looked at her face, and my heart gave a leap. I’ve found my queen! The figure has been finished for a long time, but her face is still temporary. – Mr. Nogin pointed at a monumental statue. – If you agree, let us fix an appointment. If you pose for me, the queen will bear your face. – What a strange proposal! the stunned Varvara said.

We have recently married with my husband in an Orthodox cathedral on the bank of the Danube. And although I of course do not know the “Song about the Nibelungs”, but in all my life I felt an attraction to Gothic art and to old castles. ... Even in my songs I draw from the cults of the ancient hunters and fishermen, and I bear the clothes of the ancient Slavs. Precisely this makes Varvara different! And you have felt this! How peculiar! – What is peculiar is that coming home to Moscow I have seen precisely you on the TV. I do not work too much in Russia. I have one statue in the cathedral of Christ the Saviour, but all my major works are in Austria. For example, the statue of Marcus Aurelius ... But the monument in the crook of the Danube will be the main work of my life. We’ve designed an unusual illumination around it, and music will emanate from every part of the statue, the rumble of vehicles and clash of weapons – the illusion of full life. I’m sure that this work will survive for centuries. And the more than three meter high “Varvara” will stand there, looking far away, through ages, fogs and rains.”

We have recently married with my husband in an Orthodox cathedral on the bank of the Danube. And although I of course do not know the “Song about the Nibelungs”, but in all my life I felt an attraction to Gothic art and to old castles. ... Even in my songs I draw from the cults of the ancient hunters and fishermen, and I bear the clothes of the ancient Slavs. Precisely this makes Varvara different! And you have felt this! How peculiar! – What is peculiar is that coming home to Moscow I have seen precisely you on the TV. I do not work too much in Russia. I have one statue in the cathedral of Christ the Saviour, but all my major works are in Austria. For example, the statue of Marcus Aurelius ... But the monument in the crook of the Danube will be the main work of my life. We’ve designed an unusual illumination around it, and music will emanate from every part of the statue, the rumble of vehicles and clash of weapons – the illusion of full life. I’m sure that this work will survive for centuries. And the more than three meter high “Varvara” will stand there, looking far away, through ages, fogs and rains.”The enthralling song – as it was made explicit in another interview by Varvara – was the Grezy lyubvi (Dreams of Love). Unfortunately we could not see the clip, but from the graphics of Varvara’s site we can imagine what was that visual world that Nogin felt akin to his own.

And if it was established that one of the main figures was a portrait, we cannot brush aside the idea that the other one was it as well, namely that of the creator himself – whom we see here on the small picture at the inauguration of his monument to Vrubel in Omsk –, in the main character of the main work of his life. Is it possible that in the figures of the Burgundian Kriemhild and Attila the Hun – or, to borrow the original metaphor of Landeshauptmannstellvertreter Gabmann, in the encounter of East and West – actually two celebrities of the Moscow art scene make a rendezvous in Tulln, on the bank of the Danube?