![]() At dusk I am standing in front of the Staatsbibliothek with two large bags of loan books on my shoulders. I’m looking on my mobile which bus comes first. I hear a shy voice behind me: “Would you like an apple?” I turn around and see the speaker matching the voice, a small, shy, thin-faced homeless person who offers me a beautiful red-yellow apple. I don’t want to deprive him of this beauty. “No, thanks.” “And do you have an euro for me?” he asks in elegant German. I dig in my pockets. I hate coins, I usually try to get rid of them as soon as possible, but luckily now I find a two-euro piece. While I’m searching, he tells me that he really likes apples, but the other day he almost choked on one, it got stuck in his throat and he could barely cough it out. As he talks, I can see that he only has one tooth like in the cartoons. It is difficult to safely eat apples like this. He thanks me for the coin, and offers me the apple once more. I turn it down once more, although later I recall that maybe I should have done better to him by accepting it. “Then let me give you something else”, he says. He begins to search his infinite number of pockets. He cannot find it. He searches through them again. I know this, I have exactly the same number of pockets. After a while, I say: “It’s okay. Next time”, I almost add inshallah, since this year I have guided mainly in Muslim countries this far. I start to go towards the subway. After some two hundred meters, I hear his muffled voice behind me: “Hallo, guter Mensch!” I turn around, he reaches me. He reaches out his clenched fist. “This is it. I have found it. I don’t know whether it is made of gold or not. Maybe it brings luck, maybe not.” He pours it into my hand. I say thanks, einen schönen Abend noch. I only look at it in the light of the lamp.

At dusk I am standing in front of the Staatsbibliothek with two large bags of loan books on my shoulders. I’m looking on my mobile which bus comes first. I hear a shy voice behind me: “Would you like an apple?” I turn around and see the speaker matching the voice, a small, shy, thin-faced homeless person who offers me a beautiful red-yellow apple. I don’t want to deprive him of this beauty. “No, thanks.” “And do you have an euro for me?” he asks in elegant German. I dig in my pockets. I hate coins, I usually try to get rid of them as soon as possible, but luckily now I find a two-euro piece. While I’m searching, he tells me that he really likes apples, but the other day he almost choked on one, it got stuck in his throat and he could barely cough it out. As he talks, I can see that he only has one tooth like in the cartoons. It is difficult to safely eat apples like this. He thanks me for the coin, and offers me the apple once more. I turn it down once more, although later I recall that maybe I should have done better to him by accepting it. “Then let me give you something else”, he says. He begins to search his infinite number of pockets. He cannot find it. He searches through them again. I know this, I have exactly the same number of pockets. After a while, I say: “It’s okay. Next time”, I almost add inshallah, since this year I have guided mainly in Muslim countries this far. I start to go towards the subway. After some two hundred meters, I hear his muffled voice behind me: “Hallo, guter Mensch!” I turn around, he reaches me. He reaches out his clenched fist. “This is it. I have found it. I don’t know whether it is made of gold or not. Maybe it brings luck, maybe not.” He pours it into my hand. I say thanks, einen schönen Abend noch. I only look at it in the light of the lamp.

Luck

Hagia Sophia through the back door

![]()

In July 2020, Turkish President Erdoğan restored by decree the mosque status of the Hagia Sophia Cathedral, which was transformed into a mosque in 1453, after the capture of Constantinople, and then into a museum in 1934 by Atatürk’s decision. This decision, by which Erdoğan sought to favor his conservative voter base and illustrate his own authoritarian power, sparked protest around the world. The public nature of the museum made it a kind of bridge between cultures and religions, and its non-denominational accessibility symbolized that it was not only part of Islam, but of the world’s heritage, a common cultural treasure of humanity. Sharia, of course, does not recognize such categories. But what will happen to the beautiful Byzantine mosaics rediscovered after 1934 and made publicly visible, which are obviously incompatible with an active mosque, since this is why they were whitewashed in 1453? And how can hundreds of thousands of tourist visit a cult place that serves prayer? Erdoğan dismissed these problems: “Like all our mosques, the doors of Hagia Sophia will be wide open to locals and foreigners, Muslims and non-Muslims”, he said. That promise has since been proven to be a lie.

In July 2020, Turkish President Erdoğan restored by decree the mosque status of the Hagia Sophia Cathedral, which was transformed into a mosque in 1453, after the capture of Constantinople, and then into a museum in 1934 by Atatürk’s decision. This decision, by which Erdoğan sought to favor his conservative voter base and illustrate his own authoritarian power, sparked protest around the world. The public nature of the museum made it a kind of bridge between cultures and religions, and its non-denominational accessibility symbolized that it was not only part of Islam, but of the world’s heritage, a common cultural treasure of humanity. Sharia, of course, does not recognize such categories. But what will happen to the beautiful Byzantine mosaics rediscovered after 1934 and made publicly visible, which are obviously incompatible with an active mosque, since this is why they were whitewashed in 1453? And how can hundreds of thousands of tourist visit a cult place that serves prayer? Erdoğan dismissed these problems: “Like all our mosques, the doors of Hagia Sophia will be wide open to locals and foreigners, Muslims and non-Muslims”, he said. That promise has since been proven to be a lie.

At the time of the decision, these questions were not relevant, because the country was still closed to tourists due to Covid. When it was possible to travel again in 2021, I visited the cathedral with curiosity. The change was big. You could enter the building without a ticket, but only to the lower level. The gallery with most of the mosaics was closed to visitors. Many people were praying in the mosque. The prominent mosaics visible from here – the image of the Mother of God with the child Jesus on the vault of the apse, above the current mihrab, and the archangel Gabriel on her left – were covered by stretched canvases.

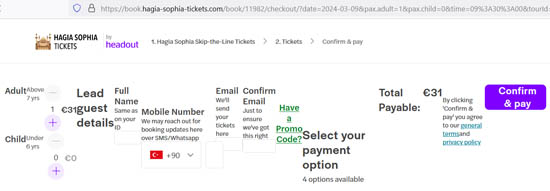

Before our current trip to Istanbul, news spread that the gallery had been opened. We visited the cathedral again with curiosity. The result, to put it kindly, is half-baked. The lower level can be entered only by Turkish citizens – so much for Erdoğan’s promise. The entrance to the gallery is on the back side of the church, from the side towards Topkapı Sarayı. It is a makeshift tunnel with electronic access gates. The ticket office is opposite the tunnel, with a long line in front of it for the €25 ticket (which is more expensive than the most expensive Western ticket I know, the one for the Vatican Museum). Tickets can supposedly be bought online, but according to the local guards, it is not recommended, because the electronic entry gate often does not recognize the electronic ticket code. In such cases, the ticket is reset, and a new one must be purchased by waiting for your turn in the line.

Later, I experience that online ticket buying is virtual in the strict sense of the word. In some of the overlappingmandatory sections of the poorly designed website it is simply impossible to enter data. Thus, the queue is the only way to go.

When you are finally inside, a spiral staircase takes you directly to the gallery. It has a gently sloping, knurled surface. It was obviously used for bringing up construction material fifteen hundred years ago.

You can walk around the gallery and see everything: the mosaics depicting the emperors and their spouses, the beautiful Deesis mosaic, the pictures of the three church fathers on the wall of the northern gallery facing the interior, the Viking runes scratched into the marble of the southern gallery by the bored bodyguards.

Christ Pantokrator, with Empress Zoe and her third husband, Constantine IX Monomachus on either side. Made between 1028 and 1042. The mosaic originally depicted her first husband, Romanos Argyros. Only the head was replaced in 1042 for that of her third husband.

Christ Pantokrator, with Empress Zoe and her third husband, Constantine IX Monomachus on either side. Made between 1028 and 1042. The mosaic originally depicted her first husband, Romanos Argyros. Only the head was replaced in 1042 for that of her third husband.

The Mother of God, with Emperor John Komnenos and his wife Eirene (the Hungarian Piroska, daughter of St. Ladislas, King of Hungary) on her both sides. To the right, on the turning wall, the heir to the throne, Alexios, who died early. Made between 1118 and 1143

The Mother of God, with Emperor John Komnenos and his wife Eirene (the Hungarian Piroska, daughter of St. Ladislas, King of Hungary) on her both sides. To the right, on the turning wall, the heir to the throne, Alexios, who died early. Made between 1118 and 1143

Deesis, i.e. the plea of the Mother of God and Saint John the Baptist to Christ the Pantokrator. It was made in 1261, after the reconquest of Constantinople from the Crusaders. John’s title “ὁ πρόδρομος”, the forerunner is translated as “pioneer” by the informative inscription

Deesis, i.e. the plea of the Mother of God and Saint John the Baptist to Christ the Pantokrator. It was made in 1261, after the reconquest of Constantinople from the Crusaders. John’s title “ὁ πρόδρομος”, the forerunner is translated as “pioneer” by the informative inscription

You can also look down on the lower level, and you can see how Turkish citizens – most of them tourists just like you, no one is praying, so the segregation is more discriminatory than religious – are walking around in the mosque. However, you cannot go down.

And some pictures from 2021, when foreigners could admire the church also from the lower level:

This is a particularly big loss for us Hungarians. After all, on either side of the mihrab stand the two large bronze candlesticks that King Matthias had made in Buda in Italian Renaissance style, and which Sultan Suleyman took from the Church of Our Lady in Buda Castle after the sacking of the city in 1526, along with the library, weapon collection, bronze statues and the library of Matthias’s palace as well as with the treasures of the churches of Buda and Pest. Until now, you could admire them up close, and even a sign proved their coming from Buda. Now, viewed from the gallery, they are almost indistinguishable in the covering of cult objects. As if we had been robbed a second time. Along with all of humanity.

At the same time as the Hagia Sophia, the greatest treasure of Byzantine art, the Chora church, was also reclassified from a museum to a mosue, even though its mosaics had only recently been restored with many years of work. It was also closed immediately, and since then noises of work can be heard from it. It is rumored that it will also be opened within a mont or two. But there, all the mosaics are in the cult space of the mosque. I wonder what the combination of violence, stupidity and hypocrisy experienced in Hagia Sophia will result there?

magyarul

Motherland from below. Photos by Dmitry Markov

![]() “They say I photograph «Russia without embellishment». But I find that quite superficial. I feel it more accurate that I photograph «the average Russia», because this is what Russia looks like beyond the great cities.”

“They say I photograph «Russia without embellishment». But I find that quite superficial. I feel it more accurate that I photograph «the average Russia», because this is what Russia looks like beyond the great cities.”

“Comparing your Instagram page https://www.instagram.com/dcim.ru with other, colorful, bright pages, one has the feeling to see two different countries. Are the heroes of your photos the real Russia?”

“Look, my grandmother just died. She worked as a seamstress in a factory all her life. Under the bed where she spent her last two weeks, we found a bag of potatoes. She has been sewing such bags all her life. This is how my gradmother’s life passed. I don’t think that today’s young people dream of such a future, of working in a factory all their lives and dying with a bag of potatoes under their mattress.

But as I take pictures like these of these aunts, of my grandmother’s potato sack, I want to see meaning and beauty in it. These pictures show people’s lives, this is how people live. And not one or two or three persons, but the majority in Russia. This is what I want to show. The newsstands show pictures of stars. I want to show ordinary people, the beauty in ordinary, everyday life."

Dmitry Markov’s interview of 2018 emphasizes beauty in these images. We are primarily struck by the misery, wretchedness and hopelessness in them, with which this beauty and humanity tries to maintain a balance. The inhumanity into which this regime pushed this people and which it uses to push other peoples into it. The source of the darkness that has flooded the world more palpably than ever before in the last two years.

In addition to beauty and love, another important feature of these images is that they shed light on stories and identities that differ from the narrative of power. They are fallible and fragile, but they are real. They are alive, full of humor and absurdity. You can identify with them. Their contrast with the symbols of power often make the latter comic. Markov calls this “alternative or protest patriotism”.

“He was a «Russian Cartier-Bresson»”, said Kirill Serebrennikov, a leading Russian theatre director who collaborated with Markov. “He was able to capture the soul of the people, their DNA. If you want to understand Russians, you should look at Dima Markov’s photos.”

Markov lived in Pskov, photographed all over Russia, and had exhibitions in Moscow, Paris, Rome and New York. He was an advertising face of iPhone 7 – he also took most of his photos with an iPhone. This was a conscious choice: this is how he was able to take such close-up pictures of people and situations. His Instagram page has more than eight hundred thousand followers.

He did not just photograph this absurd and miserable world with love, but he also wanted to improve it. Since 2007, he has worked as a volunteer in a psycho-neurological institute near Pskov, preparing orphaned children for integration into society. “We managed to save all the more or less intelligent ones”, he says in an interview. And after he was arrested at a pro-Navalny demonstration in 2021, he took his most successful photo of a masked riot police officer under Putin’s photo at the police station. He put the picture up for auction, and transferred the two million rubles he received for it to human rights organizations that help the illegally detained.

Dmitry Markov, one of the greatest contemporary Russian photographers, died on February 16, at the age of 41, in Pskov.

“Rest in peace, Brother”, writes one of his followers under his last Instagram photo. “I don't even know how to write this. You and Lekha were my beacon in this hopeless hell…”

Yury Dug’s interview with Dmitry Markov, 2019

magyarul

The Koubba

![]() The history of Morocco is a succession of capitals. The successive dynasties, having overthrown the previous one, always create a new capital in their own tribal territory, spectacularly humiliating the city of their defeated opponent, looting and destroying it, and tearing down and carrying away the marble covering and decoration of their royal buildings and mosques to decorate the ones of the new capital.

The history of Morocco is a succession of capitals. The successive dynasties, having overthrown the previous one, always create a new capital in their own tribal territory, spectacularly humiliating the city of their defeated opponent, looting and destroying it, and tearing down and carrying away the marble covering and decoration of their royal buildings and mosques to decorate the ones of the new capital.

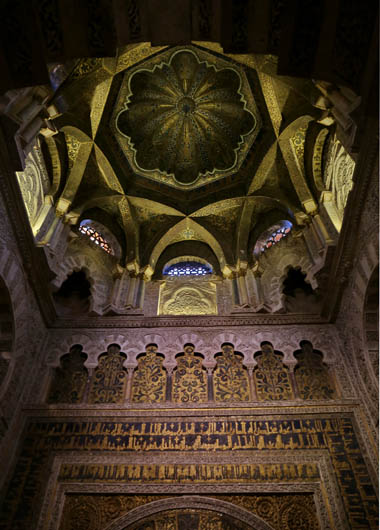

Marrakesh was founded in 1070 against the northern Fez by the Berber Almoravids coming from the nearby Atlas valleys. Organized by fanatical Muslim preachers, this dynasty quickly took control of the trade routes south of the Atlas, along which gold flowed from the Ghana empire to Morocco. Then, with this military and economic background, they easily occupied Andalucia, where the golden age of the Cordoban caliphs ended around this time. Marrakesh became the center of a rich world empire spanning two continents, and the first Almoravid caliph ruling from here, Ali ben Youssef (1106-1143), tried to make the city worthy of this rank. This ruler, born of an Andalusian Christian mother and raised in a cultured Andalusian environment in Ceuta, saw Córdoba as his role model. He tried to build the first mosque of Marrakesh on the model of the Great Mosque of Córdoba, bringing architects and even building elements – capitals and marble carvings – from there, including from Medinat al-Zahra, the Cordoban caliphate city looted and destroyed by the Almoravids.

Marrakesh was founded in 1070 against the northern Fez by the Berber Almoravids coming from the nearby Atlas valleys. Organized by fanatical Muslim preachers, this dynasty quickly took control of the trade routes south of the Atlas, along which gold flowed from the Ghana empire to Morocco. Then, with this military and economic background, they easily occupied Andalucia, where the golden age of the Cordoban caliphs ended around this time. Marrakesh became the center of a rich world empire spanning two continents, and the first Almoravid caliph ruling from here, Ali ben Youssef (1106-1143), tried to make the city worthy of this rank. This ruler, born of an Andalusian Christian mother and raised in a cultured Andalusian environment in Ceuta, saw Córdoba as his role model. He tried to build the first mosque of Marrakesh on the model of the Great Mosque of Córdoba, bringing architects and even building elements – capitals and marble carvings – from there, including from Medinat al-Zahra, the Cordoban caliphate city looted and destroyed by the Almoravids.

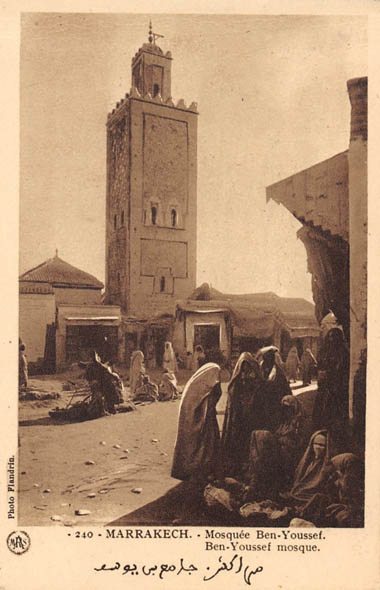

The Ben Youssef Mosque still stands to the north of the bazaar. However, this is no longer the one built by Ali ben Youssef. The Almoravid mosque, along with the entire city, was destroyed by the next fanatical Berber dynasty, the Almohads, after the capture of Marrakesh in 1147. Then the mosque built on its place and destroyed again, was rebuilt again by the Saadi dynasty in the 1550-70s, and then by the Alawi dynasty in the early 19th century.

The Ben Youssef Mosque still stands to the north of the bazaar. However, this is no longer the one built by Ali ben Youssef. The Almoravid mosque, along with the entire city, was destroyed by the next fanatical Berber dynasty, the Almohads, after the capture of Marrakesh in 1147. Then the mosque built on its place and destroyed again, was rebuilt again by the Saadi dynasty in the 1550-70s, and then by the Alawi dynasty in the early 19th century.

However, just as there are survivors of every destruction, who survive by hiding in basements, locking themselves in warehouses, pretending to be dead, so there are three survivors of Marrakesh’s first heyday.

One is the Almoravid mimbar – pulpit –, one of the masterpieces of Islamic art, which Ali ben Youssef ordered in Córdoba in 1137, and which the Almohads took to the Kutubiyya mosque built by them, which is why it is usually referred to as the Kutubiyya mimbar.

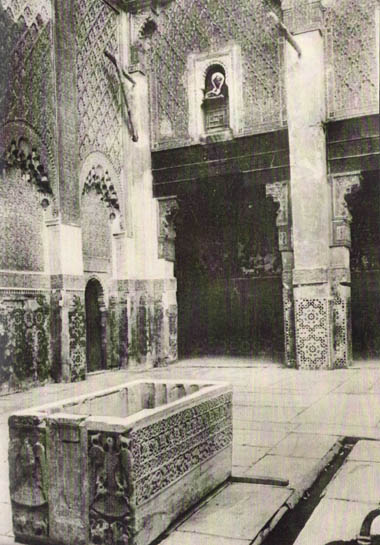

The other, also imported from Córdoba, is a marble water tank richly carved with vegetal patterns and animal figures, once used for ritual ablution. According to its inscription, it was ordered by Abd el-Malik ben El Mansour, courtier of the Cordoban Umayyad caliph Hisham II, between 991 and 1008. It was probably brought from there by Ali’s father Youssef ben Tashvin, after the sack of the city. Today it is in the Ben Youssef madrasa or theological school, next to the above mosque, which I will write about soon.

The other, also imported from Córdoba, is a marble water tank richly carved with vegetal patterns and animal figures, once used for ritual ablution. According to its inscription, it was ordered by Abd el-Malik ben El Mansour, courtier of the Cordoban Umayyad caliph Hisham II, between 991 and 1008. It was probably brought from there by Ali’s father Youssef ben Tashvin, after the sack of the city. Today it is in the Ben Youssef madrasa or theological school, next to the above mosque, which I will write about soon.

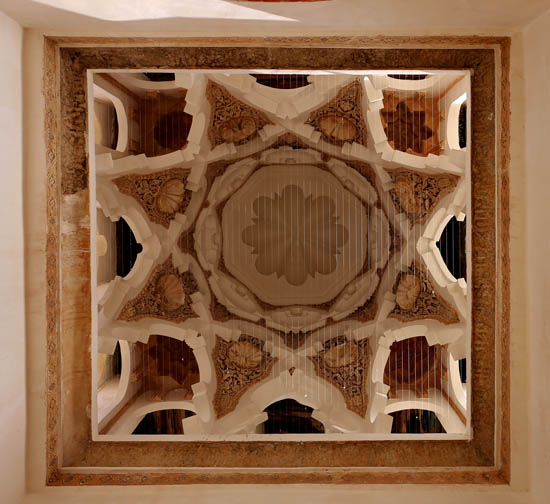

And the third is the Koubba. This word, meaning “dome”, traditionally denotes a tomb. This small architecture, however, was not built as a tomb, but as a pavilion for ritual ablution, a midaʿa, in front of the Ben Youssef Mosque. At the bottom it had a basin for washing, and it was surrounded by latrines and basins for giving water to animals. In this way, it was not only a religious, but also a public service institution for the bazaar that extended south of the mosque. This is probably why it was saved. The bazaar gradually grew around it and covered it, while the ground level that rose at a height of 7-8 meters due to the destruction, covered its entire lower part. It was only in the first half of the 20th century that they began to excavate and free it form the stalls built on top of it. It was restored in recent decades and has been open to visitors since last February.

And the third is the Koubba. This word, meaning “dome”, traditionally denotes a tomb. This small architecture, however, was not built as a tomb, but as a pavilion for ritual ablution, a midaʿa, in front of the Ben Youssef Mosque. At the bottom it had a basin for washing, and it was surrounded by latrines and basins for giving water to animals. In this way, it was not only a religious, but also a public service institution for the bazaar that extended south of the mosque. This is probably why it was saved. The bazaar gradually grew around it and covered it, while the ground level that rose at a height of 7-8 meters due to the destruction, covered its entire lower part. It was only in the first half of the 20th century that they began to excavate and free it form the stalls built on top of it. It was restored in recent decades and has been open to visitors since last February.

In the aerial photo from 1930-31, the Ben Youssef Mosque is in the middle, with the newly excavated Koubba in front of it

In the aerial photo from 1930-31, the Ben Youssef Mosque is in the middle, with the newly excavated Koubba in front of it

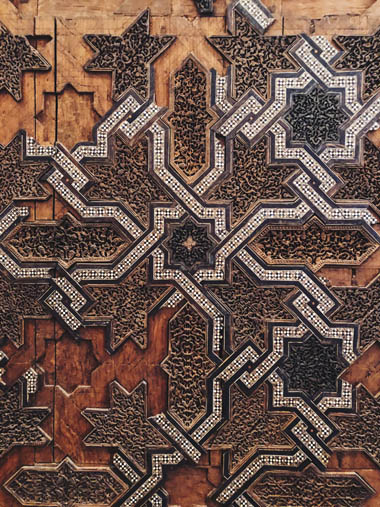

The lower part of the building opens onto the pool with two horseshoe-arched gates on the longer sides, and one multi-leaf gate on the shorter sides. The internal arches of the latter are decorated with a beautiful geometric pattern. On its inner cornice, a Kufi inscription dating back to 1125 runs around, gloryfing Allah andd the builder Ali ben Youssef.

On the longer side of the upper part, there are five alternately multi-leaf and horseshoe-arched windows, while on the narrower side two multi-leaf ones. The dome rises above the upper, fringed cornice, whose complicated brick architecture, as we will see, is purely decorative and does not reflect its real architecutre visible from the inside.

The windows illuminate the lower part of the dome. This dome is the most special element of the koubba. It is supported by intersecting multi-leaf arches starting from the third points of the cornice. The arches transform the square into an octagon, and then into the beehive-like dome. The undecorated white surfaces of the arches, the octagon and beehive emphasize the structure, while the infill surfaces between them are covered with colored stucco, acanthus and palm leaves, with an accented central shell on each of the eight eaves. This structure is obviously a development of the mihrab, prayer niche of the Great Mosque of Córdoba, but it is even more special as far as it solves the basic problem of all domes, the squaring of the circle without the intervention of a tambour, the intermediate element usual in Western domes that transforms the square into a circle.

The entire architecture cannot be well photographed. From the street, you can only see the upper part, while up close is difficult to capture in a picture.  Its prominent point of view is the roof terrace of the Les Almoravides café to the west of the mosque, from where it is clearly visible how it is located at the entrance of the bazaar, surrounded by the market, but keeping a small distance from it, and lowered, as a witness to a former city on a different level not only in space, but also in time.

Its prominent point of view is the roof terrace of the Les Almoravides café to the west of the mosque, from where it is clearly visible how it is located at the entrance of the bazaar, surrounded by the market, but keeping a small distance from it, and lowered, as a witness to a former city on a different level not only in space, but also in time.

magyarul